Does the term “photosynthesis” ring a bell? It is often termed as the fundamental phenomenon behind the existence of the vast majority of life on earth. In the context of biomass (e.g., plants/trees), photosynthesis refers to the process of using carbon dioxide, water and sunlight to create oxygen and sugar. Water from the roots of biomass is used for photosynthesis and carbon dioxide is absorbed from the atmosphere. The absorption of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere forms the fundamental basis for the concept of “biogenic carbon” employed within life cycle assessment methodology and greenhouse gas accounting.

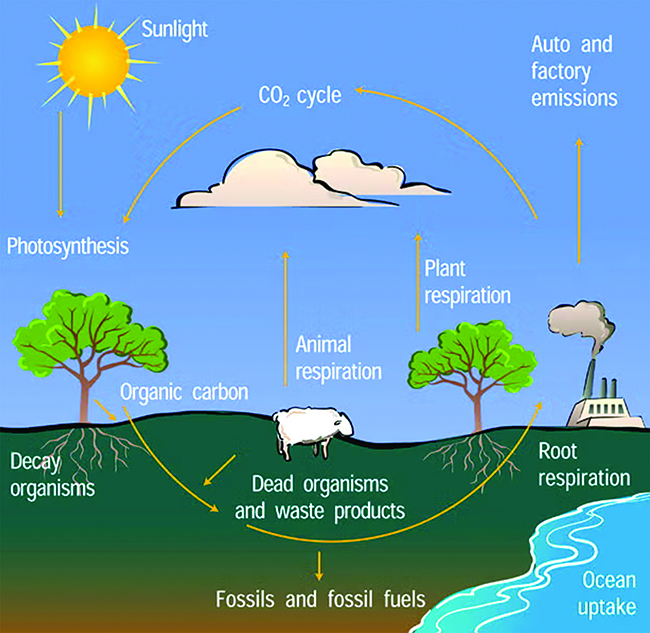

Biogenic carbon is formally defined as carbon that is absorbed and stored by organic matter (e.g., plants/ trees) and released into the atmosphere and ecosystem through decomposition or combustion. The figure below shows an example of carbon cycle listing biogenic carbon as well as other carbon exchanges such as animal respiration. An important point to note is that biogenic carbon includes carbon atoms found in both carbon dioxide (CO2) and methane (CH4) molecules and not limited to carbon dioxide. The topic of biogenic carbon is relevant within environmental sustainability quantification (e.g., Environmental Product Declaration (EPD)) of asphalt binder that may contain bio-based modifiers/extenders (shall be referred to as “bio-based additives” throughout the article). The specifics on accounting for biogenic carbon within life cycle assessment methodology and greenhouse accounting can be found in these references1,2,3,4.

Previous editions of the magazine have defined sustainability in the context of asphalt binder (holistic four pillars: performance, economy, environmental and social impacts). Hence, when viewing the concept of biogenic carbon, it is paramount to consider relevance within the four pillars:

Performance

Petroleum-based asphalt binder is used in various applications such as pavements, roofs, waterproofing and others. Decades of rigorous research and engineering have led to the development of material specification standards for petroleum-based asphalt binder. Asphalt binder is an organic material that is a complex mixture of hydrocarbons— saturates, aromatics, resins and asphaltenes—along with heteroatoms such as sulfur, nitrogen and oxygen. The relative proportions of these components determine the physical and chemical properties of petroleum asphalt, including its viscosity, adhesion, flexibility, and durability.

Understanding the composition is crucial for tailoring petroleum asphalt formulations for specific applications and performance requirements in road construction and roofing.

The tools commonly used to characterize petroleum asphalt binders for the Performance Grade (PG) asphalt binder specification rely on assumptions that the binder will be homogeneous, isotropic, free of particles larger than 0.25 mm and will exhibit linear viscoelastic behavior. If bio-based additives do not conform to one or more of these assumptions, then modifications to test procedures and practices may be necessary to properly characterize their behavior.

Bio-based additives may be obtained from plant-based, animal-based, organic waste-based, dedicated energy crops, waste oils and fats and microbial biomass. Biobased additives are commonly produced through pyrolysis or hydrothermal liquefaction. Initial laboratory studies on bio-based additives have shown promising low and intermediate-temperature performances, however, concerns exist around their high-temperature performance due to excessive moisture content. In addition, the properties of bio-based additives have been shown to significantly vary depending on the original source and extraction method 5,6.

Economics

A material value-chain’s supply-demand economics play a crucial role in their reliable availability and use over time. Petroleum based binder and bio-based additive streams are no different. The average cost of petroleum asphalt binder in North America was $565 per ton in 2024, fluctuating between $450 and $600 per ton. The average cost of bio-based additives (e.g., lignin) was around $1,000 per ton in 2024, with a range of $800 – $1,300 per ton. The absence of long-term performance warranty based contracting mechanisms hinders incentivizing/disincentivizing of constructing and maintaining high-quality pavements. Consideration of whole life cycle perspective would facilitate optimizing context-specific identification of economic savings by optimizing combinations of preservation, maintenance/rehabilitation and reconstruction treatments.

Existing financial incentives, such as Environmental Cost Indicator (ECI)7, introduced in countries like the Netherlands, are too narrow in scope, not focusing on the whole life cycle environmental and economic savings. ECI is equal to an aggregated monetary amount highlighting the negative effect of various environmental impacts. ECI for construction materials in the Netherlands could be seen as an extended version of the social cost of greenhouse gas emissions for which the United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) published updated costs in 20238.

The primary implications of policies such as ECI on asphalt binder supply-chain economics are that an additional environmental cost is levied for selling petroleum-based asphalt binder (i.e., Total cost = selling price plus ECI). However, there is no mechanism to disincentivize if the bio-based materials do not meet the expected performance and result in overall higher life cycle costs. Hence, policies such as ECI should be implemented from a life-cycle cost perspective by accounting for the long-term durability of systems such as pavements or buildings.

Environmental

The concept of biogenic carbon has gained significance due to the carbon offsets that can be shown through accounting methodologies such as life cycle assessment. Life cycle assessment modeling of bio-based additives includes their upstream manufacturing, use and end-of-life impacts like that of petroleum-based asphalt binder. Pyrolysis, hydrothermal liquefaction or gasification processes are majorly used to produce bio-based additive from dry and wet feedstocks. The application of heat and pressure varies based on the source of the feedstock and needs to be accounted for a context-specific manner when modeling upstream processes for bio-based additive production.

In addition, as communicated in earlier editions, a holistic cradle-to-grave scope incorporating durability aspects needs to be considered for accurate representation of asphalt mixtures containing bio-based additives. The dynamic nature of biomass growth and depletion should also be incorporated within impact assessment methodologies. Ongoing research around this topic has focused not just on the cradle-to-gate impacts but also on use-stage and end-of-life considerations as follows9:

1. Material losses from surface asphalt mixtures containing bio-based additives.

2. Carbon emissions are sequestered by the biomass but released at the end of life from recycling different layers (e.g., wearing course, base course) of asphalt pavement containing bio-based additives.

3. Influence of temporally dynamic characterization factors as well as timeline aspects for biomass. The research has also alarmed on trade-offs that might occur when focusing on just one potential environmental impact (e.g., climate change vs freshwater use).

In addition, research highlights the need to consider broader sector-wide implications while prioritizing the most environmentally sustainable option. An example discussed is prioritizing sustainable use of black liquor obtained during the production of paper. Black liquor is a source to produce kraft lignin, which may be used as a bio-based additive along with asphalt. However, black liquor could also be used as a substitute for natural gas during the pulp milling process. Research has shown that kraft lignin produced using natural gas results in higher environmental impacts than that using black liquor9. Hence, pragmatic availability and optimal use of resources are key for ensuring environmental sustainability across different sectors.

Social

The use of first-generation bio-feedstocks such as oil-based crops, starch and sugar for bio-based additive production may affect the availability of resources for food production. Hence, the majority of research focuses on using second-generation feedstock (also known as lignocellulosic feedstock) such as agricultural and forestry residues and municipal solid wastes to produce bio-based additives for asphalt. However, these second-generation feedstocks also encounter challenges with land-use change and freshwater use.10 It is also important to optimize sustainable use of these secondary feedstock resources for other demand-intensive applications such as biofuels.

Hence, the availability of a resilient and scalable supply of bio-based additives is necessary to meet the ever-growing social demand for infrastructure. Public services like roads guarantee societal economic development ensuring their long-term performance are a priority for public agencies and the asphalt binder industry.

Future needs

The use of these bio-based additives is still in the research phase, with the need to examine their long-term performance under different scenarios. While laboratory tests and experimental test track data may provide simulations of field performance, actual pavement condition needs to be assessed over a long period to validate long-term performance.

There is a need to examine the influence of diverse feedstock sources on the production and use of bio-based additives. The existing specifications on petroleum asphalt binder and mixtures are based on empirical data and do not consider bio-based additives. Hence, there is a need to understand the implications of using bio-based additives along with petroleum asphalt binder and mixture within the material and performance-based specifications.

Limitations have also been noted in literature around scalability and economic feasibility of various biobased feedstocks for use in asphalt as opposed to other applications (e.g., biofuels, bioplastics). There is also a need to examine eco-toxicity and other health-related concerns with these emerging bio-based additives. The petroleum asphalt binder-based asphalt mixture is the most recycled material in the United States, and the recyclability advantage needs to be maintained with the incorporation of bio-based additives.

Bhat is the Asphalt Institute Head of Sustainability Engineering and Research.

References

1. “Best practices for life cycle assessment of BiCRS” (Jan 17, 2025) energy.gov

2. “Understanding Biogenic Carbon: The Science and Application of Biogenic Carbon in Life Cycle Assessment” EarthShift Global (2024)

3. “LCA Databases Modelling Principles”, Sphera® Managed LCA Content (MLC)(2024)

4. “Biogenic carbon and temporary storage addressed with dynamic life cycle assessment” Journal of Industrial Ecology, 17, pp.117-128 (2013)

5. “Productions and applications of bio-asphalts – A review” Construction and Building Materials, 183, pp. 578-591(2018)

6. “Sustainability in Road Construction by Using Binders Modified with Biomass-Derived Bio-Oil–A Critical Review” Transportation Research Record (2025)

7. “Environmental prices as a weighting factor in the method for determining the environmental performance of buildings” CE Delft (2020)

8. “Report on the Social Cost of Greenhouse Gases: Estimates Incorporating Recent Scientific Advances” epa.gov (2023)

9. “Kraft lignin as a bio-based ingredient for Dutch asphalts: An attributional LCA” Science of the Total Environment, 806, p.150316 (2022)

10. “Comparative study of pyrolysis and hydrothermal liquefaction of microalgal species: Analysis of product yields with reaction temperature” Fuel, 311, p.121932 (2022)